22. September 2010

TIFF 2010 Dispatches From The Toronto Film Festival

Coming Attractions

© Peter TscherkasskyFourth and Final Dispatch

And now, Perverse Comparison #2. I come very insistently to praise Raul Ruiz and Takashi Miike, not to bury them. But in some sense their latest films – exceptional achievements, both – find these bona fide form-busters burying themselves just a bit. TIFF quite wisely programmed both Ruiz’s Mysteries of Lisbon and Miike’s 13 Assassins in its Masters section, but this only begs the question. Do unruly artists achieve mastery by learning to be on their best behavior?

Gripping, fluid, and never less than gorgeous, Mysteries of Lisbon was shown in Ruiz’s 4 ½ hour theatrical cut (!); a longer version has been assembled for European television. Based on the classic 19th century novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, one of the towering figures of Portuguese literature, Mysteries is a multilayered study of paternity, power, and obscured origins. At the center of all levels of the intrigue is Father Denis (Adriano Luz) a priest with a rogue past, who has taken it as his duty to protect the bastard child of a baroness, a boy initially known only as João (João Luís Arrais). In time his true identity emerges; he is Pedro da Silva (played as a young adult by João Baptista), the illegitimate son of Contessa Angela de Líma (Maria João Bastos). Much like in the sprawling novels of the era – think Dickens, Zola, Balzac – each and every character is rendered with a richness and a depth that provides some hints at interior psychology, but is far more successful at generating a grand social skein. That is, Mysteries of Lisbon weaves a sociological tapestry, demonstrating how the interconnections between characters ultimately have less to do with chance and more to do with their common implication within a largely deterministic social and political structure, one that is all the more tenacious for its being on the wane. Ruiz, against all odds, makes every second count in Lisbon; the 266 minutes fly by, filled as they are with jarring incidents, reversals of fortune and old-fashioned costume pageantry. But there is surprisingly little of Ruiz’s narrative gamesmanship here. Even as compared with one of his most accessible efforts, the Proust adaptation Time Regained, Lisbon feels awfully «straight». There are a few moments, such as young Pedro’s early fever dream, where the visual field warps into anamorphic distortions, and the camerawork, even in the most cramped interiors, is always roving and restless, as opposed to the staid atmosphere of an old Merchant-Ivory production. But even the recent botch job Klimt displayed more auteurial verve. Nevertheless, Mysteries of Lisbon is a task few filmmakers could have tackled with such consummate skill. The film does feature stories within stories, but their function is to clarify, rather than to obfuscate – sort of a Dutch-doll Barry Lyndon. Ruiz was clearly the man for the job.

In the past, when Japanese upstart Takashi Miike has «done classicism», it’s generally been an obvious joke. His 1999 film Audition, for example, spends its first hour in a quite convincing Ozu vein, only to pull the rug out in a spectacularly horrifying manner for hour two. Likewise, the recent Sukiyaki Western Django flirted with Leone-style conventions in order to render them virtually inscrutable. By contrast, 13 Assassins is about as clean and professional a film as Miike has ever made, and it is likely to become his biggest international hit in over a decade, provided anyone’s still paying attention to him. (A Competition slot in Venice certainly didn’t hurt.) No exploding stomachs filled with half-digested noodles (Dead or Alive), no incestuous shenanigans (Visitor Q), and no women birthing full-grown men (Gozu). Just a reasonably straightforward samurai epic, expertly mounted and performed, hitting all the requisite contact points. The basics: Lord Naritsugu (Goro Inagaki) is the reigning nobleman in a large province, and his birthright and political ties make him impossible to depose despite the fact that he is a cold-blooded psychopath. He kills and tortures peasants, and the children of lower nobles, at will, and his violent ways (during this, the peaceful end-days of the Shogun era) have made him a liability who can only be dealt with by assassination. Sir Doi (Mikijiro Hira), an official who is loyal to the shogunate above any one man, plans to assemble a team of samurais to carry out the hit. His first contact is Shinzaemon (Koji Yakusho), who here occupies something akin to the Toshiro Mifune / Clint Eastwood role, although he is actually somewhat more imbricated with the samurai structure than those free radicals, having disciples and social ties. (If there is a true «man with no name» here, it is Koyata (Yusuke Iseya), the 13th assassin, a homeless wanderer and non-samurai who treats the final battle like a big joke, undercutting the other men’s pretenses to high honor. «This is nothing compared to fighting a bear!» he admonishes. Miike delivers on every satisfying promise of the genre, and provides a few surprises of his own, such as unlikely architectural weaponry and, well, flaming oxen. Nobody saw those coming. But apart from a few bracing moments, such as a sequence between Shinzaemon and a young woman mutilated by Naritsugu, Miike the old prankster has not shown up to play in 13 Assassins. Again, as with Mysteries of Lisbon, registering a complaint with the Ministry of Auteur Studies seems churlish when the films in question are so thoroughly accomplished on their own terms. Still, cinema doesn’t exactly have oddballs to spare.

By way of conclusion, some brief notes on other notable films seen over the eight days I attended the festival. After the unnerving but impressive Carcasses, a film which placed Lisandro Alonso-style observation in the context of a Quebecois junkyard and then introduced a possible murder mystery among the mentally challenged (no, really), I was quite disappointed with Curling, the latest effort by Canada’s Denis Côté. At first, it seems to be another portrait of outsiders (in this case a father and daughter) but it soon takes a turn toward the deliberate. By this I mean, there is a Secret, and once you figure it out, everything that had once been compelling and mysterious is really just a satellite orbiting around that central idea. Another self-satisfied film with too much blood on its hands, but far less on its mind, was Sion Sono’s reprehensible Cold Fish, my (unfortunate, so I’m assured) first exposure to this Japanese maverick. A 2 ½ hour cartoon of grisly proportions, the film focuses on rival tropical fish dealers in a mid-sized Japanese town, one a weak-willed nebbish despised by his second wife and teenaged daughter, the other brash, confident, and sexy – a sort of seductive Teorema figure who becomes, naturally, more tormentor than liberator. Ugly and pointless up to the two-hour mark, Cold Fish takes a nosedive when the shlemiel «becomes a man» via child abuse and marital rape. By dramatic contrast, a film that is quite blood-soaked indeed but actually engages with questions of ethics and the value of human life (even if it cannot provide satisfactory answers in the end) is State of Violence by South African director Khalo Matabane. The film is in part the story of Bobeti (veteran actor Fana Mokoena), a.k.a. «Terror», a kid from the townships who escaped and now is a bank president. His success having garnered national attention results in his ugly past revisiting him, with deadly results. But much of the film is spent with Bobedi kind of looking for revenge for the murder of someone close to him, while discovering that those he left behind have their own reasons for not comprehending who he is, who he was, and what he did. Although Matabane cannot fully articulate the stakes involved in the opposing sides in Bobeti’s struggle – in certain ways it looks like a standard «you forgot where you came from» tale – subtle hints make it clear that State of Violence bears historical signposts that would play differently in a South African context. «If we hadn’t done what we did», Bobeti remarks, «none of you would be free», which seems to indicate that he and his mates, who we’d been led to think were street thugs, were actually ANC, a distinction even the younger generation in country may fail to apprehend.

Finally, let me say something about Hong Sang-soo. If you’re going to keep making the same film over and over, 1) make it a good movie, and 2) get better at it. So while some critic acquaintances rolled their eyes at Oki’s Movie on the basis of plot alone, I am happy to cheerlead for it, as it’s one of his very best films in years, probably since Tale of Cinema. As with Tale and several other recent Hongs, Oki relies on a film-within-a-film structure, in which we see a young film professor, Jin-gu (Lee Seon-gyoon) tell his wife that he may have to do some drinking tonight, because he has a Q&A for his film. In the meantime, he gets drunk and embarrasses himself at an unanticipated faculty meeting. This sequence, A Day for Incantation, is shown to be the thesis film for a young male student also called Jin-gu (Lee again), made for Professor Song (Moon Sung-keun), an older man doubting his commitment to teaching. Both men are enamored with another film student, Oki (Jung Yumi), whose own film, Oki’s Movie, is the final of the four multiple-perspective mini-films within Hong’s master text. The final part is the most self-reflexive, and the one that cedes the most laser-sharp gender analysis to the female character, who compares and contrasts the younger and older men with a wisdom neither one possesses. As a kind of academic in-joke, Hong punctuates each segment with «Pomp and Circumstance», Elgar’s march virtually mocking the proceedings. When it comes to the school of life, try as we might, we never graduate.

Third Dispatch

I’ll leave it to others to evaluate my work as a critic; that’s not for me to say. But I will be the first to admit that I’m a terrible journalist. I tend to work too fast, and while I usually do everything I can to check all my facts – I do in fact take accuracy very seriously – I sometimes get things wrong just because I rely too much on my memory. That’s the trouble with having a good memory. I seldom take notes, and I generally get things right, but when I screw up, I have no one to blame but myself. Add dodgy Internet access to the mix, and it’s a perfect storm of error. So, first of all, I misremembered Delfina Castagnino’s film What I Most Want as having premiered at Locarno, where in fact it never played. My mistake – its premiere was at the BAFICI in Buenos Aires. It also screened in the prestigious San Sebastian festival in Spain. Secondly, by the time my last dispatch dealing with Of Gods and Men went up, the reverend in Florida who planned to hold a Koran burning relented, calling off the «event».

Also, one semi-retraction: TIFF actually selected a pretty decent German film. That would be Blessed Events (Glückliche Fügung) by Isabelle Stever. The director, who studied at the dffb and was a participant in the Deutschland 09 omnibus, appears to have semi-direct ties to the group of advanced filmmakers currently revitalizing German cinema, and whom TIFF is studiously ignoring. I wouldn’t make grant claims for the film, but there is a distinct tone at work in Blessed Events that sets it apart from many of its counterparts. If I were forced to make an immediate comparison, it would be to the work of Maren Ade, but with a sensibility at once more diffuse and mundane. Essentially a female-centered, existential-dread riff on Apatow’s Knocked Up, Events focuses on Simone (Annika Kuhl), a strangely awkward, unconventionally attractive woman (think a haunted Hilary Swank) approaching her late thirties. In the opening sequence, Stever shows us Simone riding her bicycle to the nightclub, disco dancing, getting drunk, having a one-night-stand, waking up in the guy’s car and biking home, all in an economical six or seven minutes. A frank contrivance links Simone up again with Hannes (Stefan Rudolf), a male nurse in a hospice ward. Upon this second meeting, Simone informs Hannes that she’s pregnant, and he’s pleased. And it’s off to the races, sort of. Stever’s film is deeply off-putting in its refusal to abide by narrative logic and human motivation, relying instead on anxiety-inducing agreeability that eventually stops making sense to Simone. Formally, Events makes the most of negative space (the film is nearly over before we learn Simone’s name, for example), and this mirrors the frazzling vapidity of Hannes, an art film himbo who may or may not be hiding something.

So there was one significant discovery, which is often plenty. Now, I’ve been writing and posting elsewhere about the avant-garde films I’ve been seeing here, but there are a couple that I have not yet addressed, and now is as good a time as any. One film, from the annual Wavelengths series of experimental film and video screenings, is by a master of that form and is incontestably part of «the scene», but the other is not. It falls somewhere between narrative and avant-garde cinema, and as such may not find the audience it deserves. Thus begins my rather perverse comparison between two unlikely suspects.

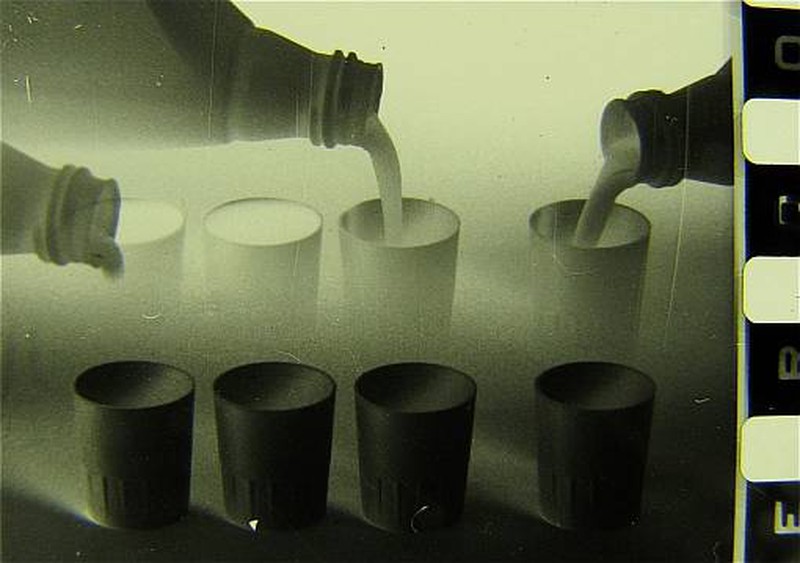

Coming Attractions, the new film by Austrian found footage manipulator Peter Tscherkassky, is exceedingly different than the Cinemascope trilogy of the previous decade. Those films, which made Tscherkassky a «star» (relatively speaking, of course) in experimental film circles, employed widescreen movies like The Entity and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly and warped their very space, exposing sprocket holes, reversing positive and negative, generating irises and frames within frames, all to produce an uncanny awareness of the act of looking. Coming Attractions takes its title, in part, from Tom Gunning’s famous film theory article about early cinema and its unique mode of internal display. Instead of maintaining an enclosed, self-sufficient story world («diegesis», if you’re nasty), early cinema actively solicits the spectator’s look. Tscherkassky’s new film, which occupies a snug, lovely Academy ratio, draws its source material from a form that, like early film and the avant-garde, openly asks to be gawked at: commercials. A bit like Peter Kubelka’s last film Poetry and Truth, but with far more complexity and variety, Coming Attractions applies some of Tscherkassky’s usual methods (reverse imagery, flicker, inter-frame cutting) to a series of comic vignettes and blackout sketches. One features a blonde model gesturing to one side of the frame, come-hither style, with her eyes, as the left-hand side of the image is replaced by a humorously random selection of attractions. Another turns a set of stage steps into a strobing pyramid; still another finds two actresses mounting white shirts to a wall to compare laundry detergent, and flubbing the reaction shots. Coming Attractions is nowhere near as tightly composed as earlier Tscherkassky films like Outer Space or Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine, but this is a good thing. It’s a bit like an Owen Land avant-comedy of perceptual errors.

Similar in its refusal to hang together but miles apart in overall mood and trajectory, Vincent Gallo’s Promises Written in Water is without a doubt the most experimental feature film I’ve seen at this year’s festival, and that includes Apichatpong’s Uncle Boonmee. Where Joe is operating within a sublime spiritual realm that is nevertheless recognizable in its oneiric pull, caressing us with a gentle imagism and sly wit that never invites mockery, Gallo’s film, like Gallo himself, is always too sincere, threatening to topple over into sheer risibility. He simply risks more, and as such he will always have as many enemies as champions. He truly «brings it on himself», but this is a component of a masochistic art of paper-light surfaces and fragile textures. It wouldn’t work quite as well if half the world weren’t ready to watch Gallo fail. Promises is a black and white para-narrative about Kevin (Gallo), a mysterious man – Drifter? Former gangster? Out of work actor? – who answers a want-ad and becomes a mortuary assistant. The funeral parlor is run by Mallory (Delfine Bafort), a young, beautiful woman who is dying and wants Kevin to fulfill her last wish – to be cremated and scattered in the river. However Gallo uses this admittedly slight narrative thread as a kind of clothesline for a number of experiments in diegetic permeability, sound / image / silence relationships, and the metaphysics of film performance. In one key scene at a diner, «Kevin» and «Mallory» discuss a phonecall to Kevin’s girlfriend. «Yeah, a called her. She’s going to Thailand, with a guy who’s 55 years old, but she told me not to worry, that no one compares to me…» But soon, Gallo is repeating the lines over and over, even going so far as to ask Bafort if he can start again. Later in the scene, the characters argue about Mallory’s promiscuity, but soon it’s clearly the actors debating the value of money. This and other scenes recall Andy Warhol’s film work, especially The Chelsea Girls and Kiss. But Gallo also has room for a raucous dance number (set to Polygon Window’s «Quoth»), a tense hotel room-pacing scene, and a beautiful nude portrait of Bafort reminiscent of Willard Maas’s early experimental short Geography of the Body. Think what you will of him personally, but Gallo is a major artist whose work has left commercial cinema far behind. He deserves to share audiences with James Benning and Thom Andersen, but at this point he seems stuck in a ghetto all his own.

Second Dispatch

Due to an ill-advised film overload, this second dispatch arrives a bit later than I’ve had liked. However, its tardiness does come with the added benefit of somewhat improved lucidity. Looking back at my first piece, I’ve overcome with shame over the excess! Use! Of exclamation! Points! It looks like it was written by a junior high school cheerleader. My apologies.

Festival reports too often zero in on little trends or commonalities among the films on display, as a pseudo-scientific way of catching the Zeitgeist in highbrow movie culture. But of course you could spend a week watching everything at the multiplex and similarities would emerge. This, too, is sociology, but the control group is not as seductive I suppose. I will say that I made the mistake of seeing Slither director James Gunn’s new film Super starring Rainn Wilson (from the U.S. version of The Office) as a schlub who decides to win back his wayward wife (Liv Tyler) by becoming a self-styled, wrench-wielding superhero. It’s unfunny and borderline misogynistic in its save-her-from-herself chivalry. But it’s also one of way too many American movies in the last two years about, well, regular schlubs who become self-styled superheroes (Kick-Ass, Special, Defendor, and even to an extent Scott Pilgrim vs. The World). Clearly, the fact that power is faceless and bureaucratic in this country produces the sense that only extraordinary gifts (or being a maniac) permits individual democratic participation, or just being noticed. Or, too many boys are geeking out on the Internet. In a different vein, I’ve now seen three films whose plots hinge (either concluding or being instigated) by a random car accident – Silent Souls, Tender Son – The Frankenstein Project, and Essential Killing. Please, friends. Drive safely!

Now, a little about some of these films. Silent Souls, by Russian filmmaker Aleksei Fedorchenko, is actually one of the most remarkable cinematic balancing acts I’ve witnessed in quite some time. It is a film that manages to incorporate an elegiac narrative movement alongside a somewhat straightforward, nearly essayistic examination of the ethnographic inheritances of the Merjan minority in Russia. The story centers on two friends who work at a paper mill. Miron (Yuri Tsurilo) is the factory director, and Aist (Igor Sergeyev) is the factory’s ID card photographer. Miron’s wife Tanya (Yuliya Aug) has just died, and he asks Aist to help him send her off according to the complex customs of the Merjan people. As we learn in Aist’s opening voiceover, he is a writer, like his father was, and he has taken it upon himself to document Merjan culture before it is gone. While this marriage of actual historical demonstration and emotional reverie could have fallen apart at any moment, seeming either didactic or overwrought, Fedorchenko succeeds in generating a hushed, mystical tone that is at the same time absolutely material, as though we are viewing a piece of living history unfolding before us. Part of this unlikely alchemy, no doubt, comes from the fact that even though everything Silent Souls shows us about the Merjans is apparently true – the «smoking», the transport of the body, the lock on the bridge – the culture, originally of Finnish stock, assimilated into Russian ethnicity in the 17th century. So Fedorchenko’s full activation of their otherness in the present day is itself a fiction, a kind of Orthodox pageant of Flahertyesque reenactment, but placed within the context of the lives of three fully realized fictional beings. So thorough is the Merjan’s «pastness» in our present, that when they stop at an Auchan hypermarket on the way back home, it’s as though time has literally stopped for them. And this isn’t a jab at capitalism so much as a melancholic draining of the spirit from life. In terms of activating the classic Eastern spirituality of the elements, the territory of Tarkovsky and Paradjanov, I kept thinking about how many other Russian filmmakers today try so hard to do what Fedorchenko appears to have done so naturally.

On the other hand, Jerzy Skolimowski’s Essential Killing, I suppose, wants to achieve some form of transcendence from its unforgiving terrain, frozen tundra, and insistence on the limits of the human body. It’s elemental, maybe, but definitely not essential. Vincent Gallo, an actor / director I actually admire despite his public pronouncements and bad boy behavior (I think he’s kind of fun to have around, actually), plays a lone Taliban fighter, trapped in a cave by three American soldiers. Forced to shoot and kill his way out, this silent, unnamed Everyarab is the subject of a Coalition manhunt that eventually drives him over the border into an unspecified snow-covered country peopled by white Eastern Europeans. Panicked, and given to context-free, Allah-filled flashbacks, the Gallo figure kills everything in sight and undergoes immense physical punishment. However, Essential Killing also sacrifices any plausible Arab masculine psychology in the name of shocking images (one toward the end is a travesty) and needless murder without cause or honor, all of which leaves a nasty, right-wing taste in my mouth. The film wants to be «above» politics, just looking at a vulnerable body apart from such considerations. But this caesura merely let ideology come flooding back in. Also, Skolimowski ends with such a preposterous «poetic» image (Siouxsie and the Banshees would reject it as too bathetic) that I’m reconsidering my admiration for Four Nights of Anna.

By contrast, Xavier Beauvois’s deeply humanistic and highly intelligent Of Gods and Men truly captures «the essential», and it has a great deal more to tell us about our present conflicts between Christendom and the Islamic world. Of Gods and Men is a classically constructed film, organized according to familiar narrative beats (the cute old monk, the man with the crisis of faith, the «good thief», etc), and for this reason it could be called middlebrow. But it actually withholds many conventional signposts that signal audience response, instead providing a patient examination of the daily circumstances of people of faith, and asking us to evaluate those circumstances and the choices we would take were we to find ourselves in similar circumstances. The film presents the true story of eight monks living in the Atlas Monastery in Algeria who were murdered in 1996. The brothers lived in harmony with their Muslim community; they provided free health care, sold honey at the local market and were often honored guests and family celebrations. Beauvois presents a picture of two faiths living side by side in total mutual respect. However, this isn’t a rosy, pie-in-the-sky ecumenical vision. What he demonstrates is that the community shares a mutual distrust of their government, the army, the Muslim extremists, and the French colonizers of the past. That is, their bond has been sealed not through ideology but through laboring side by side, as well as each group studying the tenets of the others’ faith. That is, Beauvois shows that true religious belief requires effort, not ignorant sloganeering. And so, when the Islamist fundamentalists finally arrive in the end, Of Gods and Men has already built a nearly airtight argument that, regardless of what these men with guns might believe, they do not represent Islam. They are not men of God. Particularly when writing for Cargo, I try not to be USA-centric, but it is difficult to watch a film like Beauvois’s and clear my mind of the fact that, back home, bigots are burning Korans in order to protest the construction of an Islamic cultural center in lower Manhattan, which right-wing extremists have dubbed «the ground zero mosque». I hope that everyone in the U.S. has the chance to see this film.

Finally, last time I promised a word on Godard’s Film Socialisme, and I will actually offer little more than a word or two, since I’ve now learned that it will be covered in great depth in the next issue. But on these shores, much has been made of those so-called «Navaho English», subtitles, the fragmentary, broken-English words at the bottom of the screen in lieu of a full translation. A number of people have compared them with the fragment-texts that appear in Histoire(s) du cinema, written words that also function as montage motifs. This is quite true. (Texts here include things like calling a man named Goldberg «GOLD MOUNTAIN» and shoving other words together.) But I also think that there’s another plan at work. Film Socialisme is in large part a film about the state of Europe and the movement of money. One of the opening lines asks whether money should be a public utility, like water, which in some way defines socialism. The central figure of the film, Goldberg, appears to have been a Nazi who took on a new identity (or in the current parlance, «rebranded» himself) as a Jew in Switzerland, and his young assistant is asking him about money plundered from various banks. So Godard is clearly addressing the financial crisis that bankrupted Greece (recall his statement at Cannes) and put much of the rest of Europe on the brink. And he is likening it to the discovery not so long ago that his homeland, «neutral» Switzerland, was a haven for Nazi money laundering. I’ve already gone on far too long here, but the point with the «broken» English subtitles is, Godard, I think, wants this to be an intra-European discussion, not so easily accessible to Anglo-American eyes and ears. (I am reminded of African-American barber and beauty-shop talk, hashing out racial issues that white folks would very likely spin into racism were they to overhear.) Jean-Marie Straub simply refuses to allow his films to be subtitled into English. But then, he gets ignored. (It’s like if you don’t leave a tip for bad service, the server just thinks you forgot and are a cheap bastard.) Godard, with that mile-wide mean streak on him, wanted to frustrate the hell out of us, and let us know that we were missing out on a whole lot by not speaking French, German and Russian. (Instead of leaving no tip, JLG left us a single penny. Have a nice day, exclamation point!)

First Dispatch

I find myself at a loss for how to begin this initial blog post, partially because, in spite of all my web-based writing, I’ve never actually blogged before. So I do feel as though some sort of introduction is in order, even though it feels sloppy and indulgent to me. Nevertheless, hello, I’m Michael Sicinski, a writer and critic based in the U.S., and I’ll be submitting dispatches from this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. Right off the bat, I may as well address some of the significant changes happening at the festival this year, although I also don’t want to harp on them too much, precisely because the TIFF machine is desperate for publicity of its gleaming new Bell Lightbox theatre, a beachhead in downtown Toronto for both cinema and high-priced real estate. (Luxury condos on top!) The thing isn’t quite finished yet, but it’s all TIFF wants to talk about, a big glass corporate power-object on, appropriately enough, King Street. King me! But suffice to say, with all the press venues and offices moved to whole new locales, nobody – not the press, not the volunteers, not the staff – really knows what we’re doing yet, so this, Day Two, finds us all with classic Day Six fatigue.

And then, the films! Partly due, one supposes, to the fact that the Lightbox wasn’t done, the first two days of screenings were paltry and bizarre. But I made my way through some worthy Cannes titles, and some duds. So far, the most inscrutable and dubious achievement by an old master would have to be Jørgen Leth’s Erotic Man. This semi-confessional effort by the Danish cultural institution (in addition to his filmmaking, Leth is a well-known football commentator, and for a time was the Danish ambassador to Haiti) is so startling in its lack of self-awareness, a critical viewer keeps thinking that it must, at some point, take a turn toward autocritique. But what we have is Leth’s turgid poetic reverie about succulent nubile 20-year-old women, splayed naked across beds, in Haiti, Brazil, The Philippines, Senegal, Panama, you name it. If there are brown women there, Leth is dipping his wick and waxing nostalgic. Although the director does have an eye for Playboy-style tits-and-ass cinematography, Erotic Man is a colonialist project so blinkered it’s more laughable than offensive.

By contrast, Sylvain Chomet’s Berlin entry The Illusionist is merely a garden variety «bad film», one whose ideas never come into focus and which ultimately has no compelling reason to exist. Chomet, whose lovely Triplets of Belleville channeled whimsy with no cloying aftertaste, here produces a rediscovered early script by Jacques Tati. In it we see Tati himself in his salad days as a struggling stage magician. But apart from the fact that the protagonist is Tati, there is nothing to separate The Illusionist from any number of by-the-numbers performers’ tales of life on the road. (It’s lonely and hard!) Each country is depicted as its own worst stereotype, rock and roll is seen as a crass, decivilizing influence, and the only real drama in the film is generated through unmotivated, cruel decisions by blank-slate noncharacters. The Illusionist eventually becomes a riff on City Lights, if Chaplin’s Tramp had been a complete asshole.

As for further disappointments, the less said about Delfina Castagnino’s What I Most Want, the better. Castagnino’s film generated some excitement in Locarno, and the fact that she worked with Lisandro Alonso was enough for me to consider her film worth a look. But it’s stuck between a meandering 20-something talkfest and something more formalist, resulting in a stilted Argentinean Sex and the City episode in the woods. The third acts «deepens» things, I suppose, but it’s a Hail Mary shot at profundity.

Luckily, some old masters and a few strange new upstarts came through. Among the latter, Michelangelo Frammartino already impressed many at Cannes with his experimental feature The Four Times, and while I ultimately wanted it to dig a bit deeper than it did, it was a joy to place myself in the hands of a director with such a sure-footed, rigorous sensibility. The Four Times is a tricky film to write about, because so much of its power of insinuation relies on the element of surprise. Suffice to say, this is a film about an elderly rural Italian goatherd who eventually recedes in order to reveal the different layers of reality around him. Frammartino is also, I think, interested in the presence or absence of the spiritual, and how we can exist solely within materialism and still experience wonder.

Speaking of the material and the spiritual, two other films from Cannes I caught up with in the past two days seem on the face of it to stake out opposing positions on the question, but closer examination makes the issue far less certain. On the side of the brute earth we have Ukrainian Sergei Loznitsa’s My Joy, a film that seems both to insist upon chaos and brutality as the fundamental state of things, and regard the human animal as first and foremost a piece of meat. Not that Loznitsa approves of this situation; the first half of My Joy finds a decent man traveling through post-Orange Ukraine and observing relentless abuse of the weak by the strong. Soon, though, even the idea that this brutality can be observed – that someone could stand apart and evaluate it – becomes too romantic an idea for Loznitsa to tolerate.

By contrast, Manoel de Oliveira’s The Strange Case of Angelica is a kind of cross between a miracle play and a descent into madness, all hinging on materiality becoming its opposite. Isaac (Ricardo Trêpa) is a Jewish immigrant who is called on to photograph the corpse of a young woman (Pilar López de Ayala) prior to interment. It is through his camera that Isaac begins seeing Angelica return to life, and eventually her ghost haunts his dreams and possibly more. Trading on lore of both angels and «spirit photography», Oliveira makes an unusual move into the supernatural realm, but he’s ultimately showing that even in our fantasies, it’s the physical stuff of the universe that moves us, even unto the irrational. Both films entail necrophilia, one literally, the other at the ocular remove of the camera. But – this is the cultural studies scholar in me -- I’m starting to wonder exactly what it is at this historical moment that we’re asking of the dead.